- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

feature

2021 Wilier Filante - riding 5.jpg

2021 Wilier Filante - riding 5.jpgMidlife cycling performance: too late for speed?

We older and less fit midlife cyclists are, as a group, riding harder and faster, relative to our maximum, than the top-ranked professionals in the world. And we're holding down jobs and trying to be great parents and partners.

Data from Dr Jon Baker, who was a coach with Team Dimension Data for four years, says that his amateur clients (that’s you and me) are closer to fatigue and nearer to being overtrained than the professionals who ride for a living and race nine months of the year all around the world! That statement was genuinely worthy of an exclamation mark. And underpinning this startling mismatch is a fundamental misunderstanding about how the human body works, and therefore improves.

Many amateurs perpetually train and ride in what Dr Baker calls a ‘whirlwind of doom’ where an overestimation and obsession with an FTP (functional threshold power – the highest average power output you can sustain for an hour) means that we tend to set our training levels too high and, as a consequence, are training the wrong systems and incrementally embedding fatigue that we then struggle to shake off if we're older, because our hormonal responses are less responsive and dynamic — is this ringing any bells?

Dr Dave Hulse (a consultant in sport and exercise medicine), Dr Baker, and elite coach Garth Fox all go out of their way to remind us that cycling (other than sprinting on a track) is fundamentally an endurance sport — and endurance is what we're best at compared to other animals. Recent studies have even suggested that the drive to efficiency and therefore endurance is what selectively drove us towards bipedalism. We may not be super-sprinters compared to other big mammals (I can’t think of a single one we can beat in a short burst), but we can go seriously long, which meant that we could subsistence hunt much larger prey than ourselves over multiple days.

But what constitutes endurance? Dr Baker says: “Endurance has to mean aerobic — which is determined by the strength and ability of the heart, and then the ability of the blood, to transport fuel to the muscles, and the muscles to then use that fuel.”

Aerobic, as we know, is a cipher for functioning within an oxidative state — using fatty acids and glucose as fuel with oxygen, which is metabolised in our muscle’s mitochondria to produce energy. It’s our long-burn, sustainable state. Our most important goal as endurance athletes surely has to be to increase our oxidative or aerobic performance window, to become better at producing more power but at the same time staying oxidative/aerobic.

We need to become lean, long-burn machines and the only way to achieve this is to ride at this specific level — remember that we're highly adaptable creatures and our bodies will change and improve based on specific repeated stresses.

This is where power meters and heart rate monitors can help — if we make them truly our servants and not our masters. They can help us become more honest with ourselves about our own performance and how we feel.

The best way to use a heart rate monitor or a power meter is as a bandwidth limiter. If you're oxidative all the way up to 135bpm or 160 watts, then that’s where the majority of your riding should be in order to improve as an endurance athlete. If you’re working at this level, then you’re the recipient of a cascade of positive physiological responses, including increasing the mitochondria in your muscles.

Every time you go above this level, you’re having to use enzymes to break down the excess lactate. Dr Baker's coach’s eye view: ‘If you feel good on an endurance ride, go longer, not harder. Going harder is risky. Going longer is safe. It’s the same with intervals — if you feel good, do an extra rep or two, but don’t increase the power.’

If you don’t have a power meter or a heart rate monitor, you can use the RPE (rate of perceived exertion), or Borg Scale. If you want to be a great endurance athlete, most of your training should be at a level where you can have a fairly normal conversation with the person next to you, or sing a whole verse of a song without stopping and gasping for breath. On a Borg Scale this would still be quite low — maybe 12 or 13, where 6 is lying on a bed reading a book and 20 is full effort.

You'll know if you’re ceasing to work aerobically (or, in an oxidative state) because you'll start panting or gasping if you try to sing out loud or tell anything more than a quick one-line joke. This is because when enough lactate has accumulated in your system, your brain will automatically preference breathing over talking, in an attempt to clear CO2 out of your system and bring you back into aerobic equilibrium.

It's worth pointing out that recovery from endurance rides is also easier than recovery from intense interval sessions, where the fatigue tends to be embedded. deeper into our physiological and muscular-skeletal systems. As Dr Baker puts it: “The 'hours of power' approach tends to make you more tired as the quality of your sessions declines. Ergo, if you’re less tired, you tend to miss fewer training days, which has to be good because fundamentally endurance equals volume."

Is this where old school training, my chaotic school (my basic philosophy was to ride my bike enough in the winter for adventure, fun and relaxation, to be able to race myself match fit-ish in the spring), and the new-data school intersect? We all seem to be saying the same thing. That to build yourself into a persistence (or endurance) hunter you need to train yourself to be a hyper-efficient aerobic machine, ruthless at scavenging sustainable fuel stores at as high-power outputs as possible.

It isn’t a high FTP that will get you round a big day in the mountains, it’s a high-functioning aerobic system. If you've inadvertently trained the wrong system by going too deep and too hard, you'll be producing excess lactate and utilising precious glycogen stores too quickly, which in turn will make a fit-for-purpose refuelling strategy very difficult.

Dr Baker thinks that most amateur riders function at only 60 per cent of their theoretical aerobic (oxidative) capacity due to training incorrectly — mostly from riding too much at too high a level. You need to be a fast tortoise before you can become even a slow hare.

Both coach Fox and Dr Baker agree that the majority of riding should be steady-state to increase our oxidative capacity — as much as 80-90 per cent of our training load. We have to learn to be efficient before we can learn to be fast. But even as midlife cyclists we can gain a huge amount of benefit from the correct dose of intense interval training.

Controversially, I’m going to suggest a few midlife amendments to current training orthodoxy. The first is that we drop all the other strata of training, other than low intensity (LIT) and high intensity (HIT) training. We'll define LIT as anything below aerobic threshold, which coach Fox recommends could be as high as 70-80 per cent of maximum heart rate, but thinks is actually better executed at around 60-70 per cent of maximum. Dr Baker agrees with this and adds the context that ‘it's almost impossible to go too low’ for LIT or oxidative training, meaning that the most important principle to observe is that you must actually be oxidative, which you won't be if you go too high.

You could use a heart rate monitor and use a percentage of your highest recent recorded heart rate or you could use the RPE/Borg Scale and the ‘sing-a-verse’ methodology (which I prefer, incidentally). It’s important to note that riding in an oxidative state involves metabolising fatty acids as a fuel source, which could be important if you’re also trying to manage weight as well as gain fitness.

Anything above LIT, is by definition in our binary training model, HIT. If you're using the RPE/Borg Scale, LIT is anything below 14, HIT is 15-20. Both Dr Baker and coach Fox suggest no more than one or two sessions a week, and how you configure them can be the result of your own imagination. It could be hill repeats (not imaginative but can be effective) or Dr Baker’s suggestion: “There’s gold in 8-10-minute efforts in the 105-110 per cent of FTP range. The goal is to do lots of reps, say 4-6. If you hold power steady, then your heart rate won't quite hit your maximum. So you can rest up a bit, and repeat again.”

Remember, Dr Baker is going out of his way to point out that if you feel good, you should not increase the intensity, meaning no more watts or a higher heart rate, but instead add in a rep or two. Going too deep or too hard will increase the required recovery time and may lead to fatigue. If you assume your real (not inflated) FTP is 250, then your hard sessions using the Dr Baker algorithm will be 250 x 105-110% x 4-6 (8-10 minute) reps. This means that you'll be working at between 262 and 275 watts during those 8-10 minute reps. This isn’t going bonkers and sending your systems haywire — it’s a controlled elevation of training stimulus.

Coach Fox’s thoughts on the subject of sensible restraint are these: “The important aspect (and the part that amateur athletes have enormous difficulty in executing well) is that only about 10-20 per cent maximum of training time needs to be here. This can be done as one or two harder interval sessions per week, but not more as that just leads to plateauing sooner rather than later. It really should be no more complicated than that. In fact, I would hypothesise the opposite.”

Dr Baker and coach Fox are united in the opinion that we amateurs — especially more time-constrained masters athletes, because we want to optimise our limited time — mostly train too hard when we should be working in an oxidative state and not incorporating too many intense interval sessions. Essentially, we're over-revving ourselves into aerobic inefficiency or, even worse, embedding fatigue in our bodies by riding too often, too close to threshold, and not leaving sufficient recovery time between training sessions. We’re not only burning the candle at both ends, we’re then taking a blow torch to it to make sure it’s dead.

Dr Baker and coach Fox are united in the opinion that we amateurs — especially more time-constrained masters athletes, because we want to optimise our limited time — mostly train too hard when we should be working in an oxidative state and not incorporating too many intense interval sessions. Essentially, we're over-revving ourselves into aerobic inefficiency or, even worse, embedding fatigue in our bodies by riding too often, too close to threshold, and not leaving sufficient recovery time between training sessions. We’re not only burning the candle at both ends, we’re then taking a blow torch to it to make sure it’s dead.

About the author: Phil Cavell

Phil is co-founder of Cyclefit, a vastly experienced bike fitter, and a bike designer. Phil heads up the lecturing and teaching duties at Cyclefit.

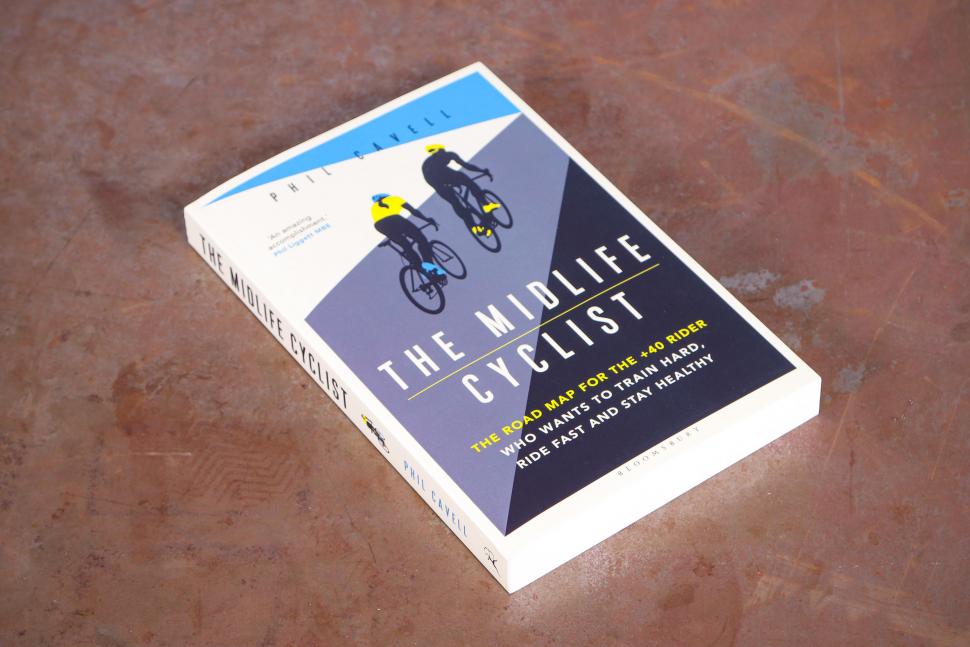

The Midlife Cyclist is available now from Bloomsbury in paperback and Ebook formats.

Latest Comments

- BBB 3 sec ago

Inhumane system that now will be getting even worse.

- Bungle_52 3 hours 23 min ago

In case anyone missed it in yesterdays blog here are the two pevious articles. The second one contains the testimony from the driver....

- David9694 3 hours 32 min ago

The old role was appointed at the Mayor's pleasure; is in addition to the permanent staff of the Combined Authority. I'm not sure if Adam was an...

- chrisonabike 3 hours 37 min ago

Ah... but which civilisation? If arguing from precedent (or even "moral ground") - with the benefit of almost no political, historical knowledge...

- WillPage 4 hours 58 min ago

Nothing says "welcoming environment" like uniformed thugs, umm I mean "security patrols " roaming the area.

- galibiervelo 6 hours 16 min ago

That is class news. Super bikes and vision. Bet there will be no stand at the Taiwan bike show next year! Big luck to all the team

- Destroyer666 6 hours 58 min ago

Pretty clearly stated several times in the text that the issue was not related just to his son. And besides, everybody watching the races could see...

- Rendel Harris 7 hours 14 min ago

All Fizik and Selle Italia saddles (though not all their other products) are made in Italy I believe, and their 3D printed models definitely are.

- chrisonabike 7 hours 40 min ago

If you're not on the road with a car, I bet its driver is much less likely to swerve into your space *. Because you're not "in the way"! (Any...

- mdavidford 7 hours 56 min ago

The problem with this argument, though, is that it's just not true....

Add new comment

15 comments

That all sounds sensible and reasonable if you have plenty of time to go long at low intensity.

What would be interesting to know is whether, if you have limited time- say 1 hour a day, 5 days a week, it is better to go hard more often, or have 3 easy hours and 2 hard hours each week.

While agreeing with everything in the article re training efforts and HIIT sessions. My advice for a regular, non hyper competitive, middle aged cyclist would be to discard all the performance metering equipment. Inevitably you will end up tracking your own decline with a constant reminder of where you once were, running in the pack with the vigorous young bucks. Instead I would suggest looking for new challenges, new skills, novelty and variety in your exercise program.

Add more time not more effort is fine if you have plenty of spare time.

The reason pros can train for longer at a lower effort is because they aren't trying to fit in some training around their job. Sneaking a few hours or minutes here and there to train.

I find it really difficult to stay in lower heartrate zones, it just saps all the fun and purpose out of most rides and is especially difficult on the gravel bike. It's causing a bit of a dilemma because I WANT to train properly for whatever the CX season throws at us, but training effectively just seems a bit joyless, sitting spinning gently up climbs or gently trundling along gravel sections when every instinct is to get on top of a big gear and smash it, etc. etc.

I guess the answer might be to plan rides for the weekend where you can trundle for most of it but 'bank' your threshold efforts for the fun bits e.g. that 10 minute long gravel secteur or that signature climb etc.

Very useful article for people of any age. Unfortunately the images were mostly decorative and an opportunity was missed to match and interplay more usefully with the text content.

This seems to be suggesting a polarised training approach although he doesn't name it as such, which generally works on a 3 zone model rather than the more regular 7 zone model but whichever is used I agree with much of what is said with the odd caveat.

I agree that the majority of training should be endurance and that should be Z1 in a 3 zone model or Z2 in the 7 zone model and going above this can lead to fatigue so that may leave you too tired to carry out the HIIT intervals on another day in the week.

I don't necessarily agree that training at Tempo/Sweetspot/Threshold is something that should be avoided, quite the contrary in fact depending on where you are in your training plan and your objectives. I prefer to do a kind of block periodisation and believe that in the later stages of base training is the time to introduce tempo, tempo bursts building to sweetspot and then threshold. Once I move closer to racing, so maybe block 4 I would then take the above approach and do little or no zone 2 in a 3 zone system or Z3/4 in a 7 zone system and keep it 80/20 or 90/10 endurance / HIIT.

VO2 max is generally rated at 106-120% so I assume the 105-110% the author recommends are lower VO2 max intervals which is what I would start in block 4

I also believe that if you are an ageing athlete (I am 63) then it is important to have more recovery weeks once the intensity gets into muscular endurance. During early base blocks I will often do a 3 weeks on 1 week recovery but once into the muscular endurance work I drop that to 2 weeks on 1 week recovery.

I think it was Sean Kelly who said "The difference between amateurs and Professionals is that when an amateur isn't going well he will train harder whereas a pro will rest."

I'm 48 and find in-season a polarised approach to cycling is the best way to keep fitness up without becoming exhausted. However, during the rest of the year life just doesn't provide the time (I average 8-10 hours week) for the amount of low intensity riding that I'd need to impove. Therefore, threshold and above is incorporated in to my riding all year round and I end up with a pyramidal training load.

I agree that polarised is a good approach during the season, particularly if you are racing. This is a pretty good video on training on less than 10 hours per week here. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-Wk0f-Bsw3E&ab_channel=DylanJohnson

Judging by the book and the comments in this thread the difference between an amatuer and a professional is that a professional will have a coach who will have the time and incentive to produce training plans that are relevant for the the rider at that particular time of their fitness/season/life, whilst the rest of us mostly have to use trial and error to find what works or settle for suboptimal.

I would imagine even a pro or their coach has to do a certain amount of trial and error. There is enough information out there in books for amateurs to have enough knowledge to be able to produce a good quality training programme that can be tweaked further as we gain that experience. There is also good enough software available for free to be able to monitor progress and learn to judge how to come into form, peak and avoid over training.

Depends what you mean by trial and error. Most of that's probably done as they come up through the ranks - by the time they turn pro they'll likely have amassed sufficient data that, barring a collapse in performance and deciding to take a whole new approach, it'd mostly be small adaptations and optimisation (which, in itself, is technically a form of trial and error, but not what most people would mean by it).

All depends on the individual. Yes in most cases, you will see a performance drop in your 40's and especially 50's. Which brings me on to the fine example of pro cyclist David Rebellin, still mixing it, still ultra competitive at 50 years of age, highlighted by top 10's this year in the Sibiu Cycling Tour and the Adiatica Ionica Race.

And it goes downhill even faster in your sixties and seventies. I'm 72 and like Andystow says below, I have two intensity levels. If I push harder it is only a matter of seconds before my puls hits the limit and I have to sit down/ease off.

As David Rebellin had a doping ban from the 2008 Olympics I have never taken him as a role model. I am not sure he is a 'fine example'.

This is handy, because as far as I can tell I only have two intensity levels: "this is fine" and "that was way too much!"