- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

feature

Jasper Philipsen wins stage 15 of the 2022 Tour de France (Zac Williams, SWpix.com)

Jasper Philipsen wins stage 15 of the 2022 Tour de France (Zac Williams, SWpix.com)No Country for Fast Men: Why is this year’s Tour de France so unkind to sprinters?

This afternoon the Tour de France peloton tackles the last of three gruelling stages in the Pyrenees, the fourth and final mountain range of the race. By contrast, on Sunday Jasper Philipsen became the first bona fide sprinter to win a bona fide bunch sprint finish since the race left Denmark a fortnight and a half ago.

The 2022 Tour de France has been especially unkind to its sprinters.

Indeed, when a group of protesters from Dernière Rénovation lay across the road 65 kilometres from Sunday’s finish in Carcassonne, mimicking their earlier and more successful attempt to disrupt the race, they brought the number of environmental protests at this year’s Tour (two) level with the number of bunch gallops (for the following hour and a half at least).

Following Wednesday’s stage to Peyragudes, there have also been as many finishes on airport runways at the 2022 Tour as flat sprint successes.

Even Philipsen’s victory on stage 15 – one that was a long time coming for the talented Alpecin-Deceuninck rider – was taken ahead of a reduced field of fast men, chastened by the constant lumpiness of the route through southern France, the searing heat, and the frenetic, chaotic racing.

Fabio Jakobsen, an emotional winner of the first road stage of this year’s race into Nyborg, finished in a large group over twenty minutes down. Lotto-Soudal’s Caleb Ewan, physically and mentally exhausted after a particularly challenging two weeks, finished dead last, 20:34 behind Philipsen.

Fabio Jakobsen wins stage two of the 2022 Tour de France into Nyborg, the first of only three bunch sprints so far at this year's race (Zac WiLLIAMS SWpix.com)

Following Mads Pedersen’s breakaway victory on a similarly up-and-down stage into Saint-Étienne two days previously, Ewan lamented the lack of opportunities afforded to the pure, thoroughbred sprinters at the Tour.

“It’s stage 13 now and we’ve only had two bunch sprints. So yeah, it hasn’t been a great Tour for the sprinters,” the exasperated Australian told reporters at the finish last Friday.

So why have the Tour’s organisers and route designers seemingly turned their back on the peloton’s fast men?

To answer that question, we have to go back to the era in which this writer fell in love with the Tour: the early noughties (yes, I know).

The routes they are a-changin’

Back in that idyllic, entirely uncontroversial period, the Tour’s route followed a rigid pattern favoured by Jean-Marie Leblanc, the race’s director between 1989 and 2006: a prologue to give the GC some semblance of structure, a series of long flat stages, another time trial, then a handful of set-piece mountain days, followed by some transition stages, more mountains, a trek up to Paris, a final race against the clock, and a curtain-closing sprint on the Champs-Élysées.

The first week of racing during the Leblanc era was almost exclusively the domain of the sprinters. In 1999, for example, Lance Armstrong’s two victories against the clock, which laid the foundations for the Texan’s now annulled first overall win, provided the bread in a sprint sandwich which included seven – yes, SEVEN – consecutive flat finishes.

Four of those were won by Mario Cipollini, whose plan to flamboyantly abandon in front of his tifosi at the finish line of the first mountain stage to Sestrières was foiled by a race-ending crash earlier that day.

Most of the next decade followed this sprinter-friendly model – the first ten stages of the 2004 Tour included eight flat finishes and, incredibly, only four climbs above Category 4 (all Cat 3s) – until Christian Prudhomme’s appointment as Tour director in 2007. That year’s race, the last route to feature Leblanc’s traditionalist fingerprints, saw the London prologue followed by six almost completely flat stages across the south of England, Belgium, and northern France.

Cavendish wins... again (Photosport International)

The 2008 route, on the other hand, was the first to implement the variation and experimentation now de rigueur in grand tour design. The prologue – the sacred cow of Tour routes since 1967 – was sensationally scrapped and replaced by, of all things, a mass start road stage, culminating in an uphill finish to Plumelec won by Alejandro Valverde. That sacrilegious grand depart was followed by back-to-back middle mountain stages before the race’s second weekend had even commenced.

Though the prologue was restored, albeit in a slightly longer 15km version (therefore ridding it of its title), the 2009 opening week was perhaps even more blasphemous, containing only three bona fide sprint stages (two won by Mark Cavendish), an uphill finish in the pouring Barcelona rain, and three stages in the Pyrenees before the first rest day in Limoges.

These changes would continue at pace. Tours of the 2010 incorporated an increasing number of small hilltop finishes and complex, deceptively difficult run-ins (a trick borrowed from the Giro and Vuelta), cobbled stages, and ambush-laden forays into the medium mountains of the Vosges, Jura and Massif Central, Prudhomme’s favoured terrain for shaking up the race and ensuring tactical intrigue.

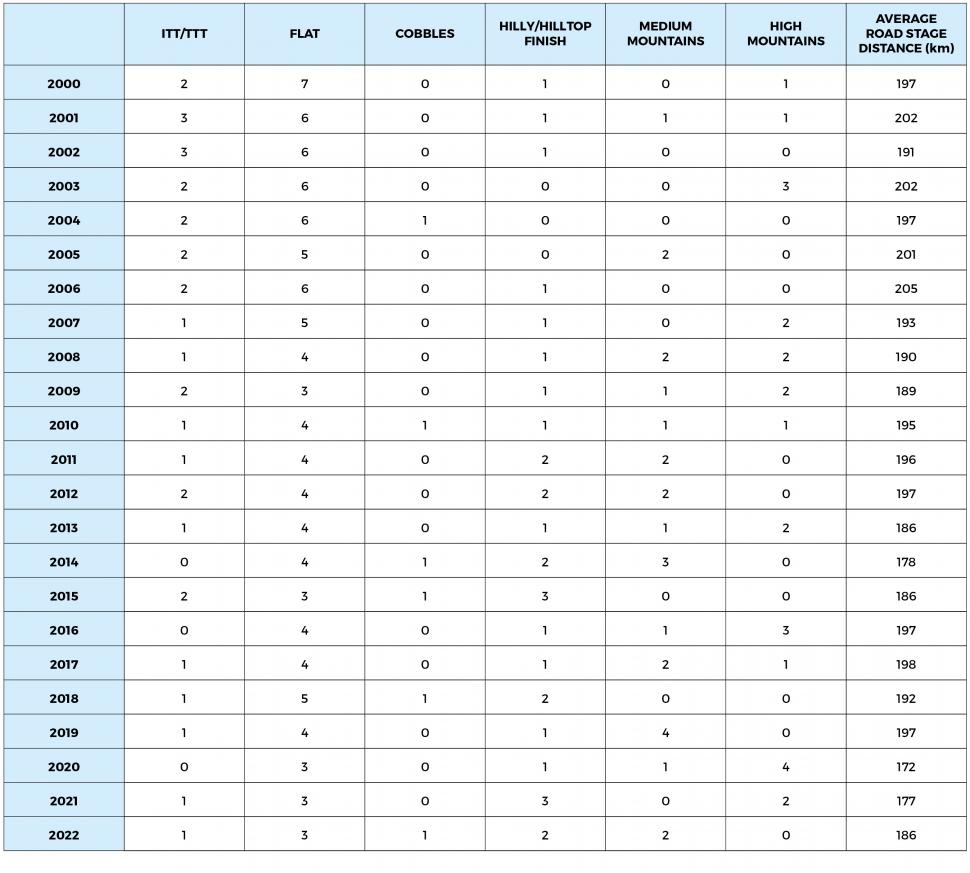

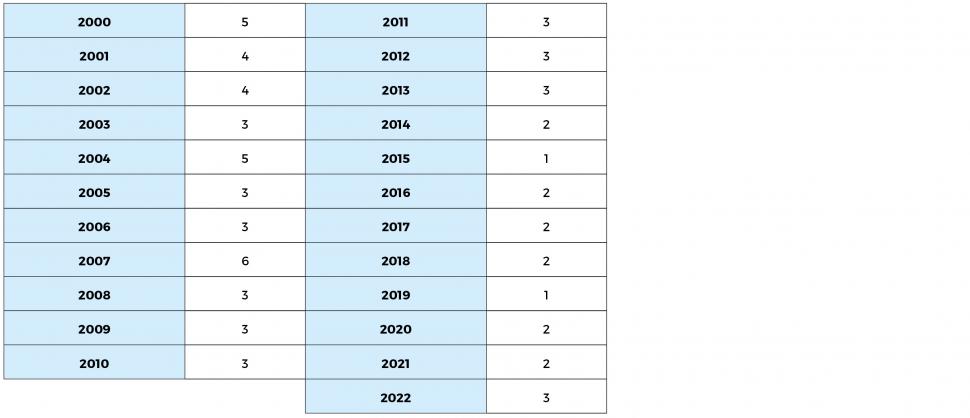

21st century Tour de France opening weeks (up to first rest day)

Stages have, in general, also become shorter and punchier. In 2006, eight stages broke the 200km mark, with three breaching 220km. This year, only three days surpass 200km, with two of those barely doing so. To underline this move away from long, endurance-focused epics (Henri Desgrange must be spinning in his grave), the earliest roll out time for a stage of the 2022 edition has been at five past noon. So much for the ‘morning break’.

Gone too, are the back-to-back sprint days which used to characterise the Tour’s opening phase. While this year’s race technically featured three consecutive flat days following the opening time trial – albeit separated by a travel day from Denmark to northern France – the last of those three stages, to Calais, included a climb difficult enough and close enough to the finish for Jumbo-Visma to explode the field and for Wout van Aert to solo away for a panache-tastic win.

Most consecutive flat/sprint days in each Tour

The slow squeezing of pan-flat days designed for the pure sprinters in favour of more dynamic, unpredictable stages has formed part of Prudhomme and route designer Thierry Gouvenou’s long-stated aim to escape what they regarded as the stale formula of previous Tours, overly reliant on time trials and set-piece mountain days. The Tour director’s ambition from taking the reins at ASO was to design a parcours of ever-present difficulty and opportunity that can be won – and lost – anywhere over the three weeks.

In that sense, this year’s Tour – a chaotic, frenetic, all-action affair with a yellow jersey battle that still hangs in the balance as the race nears its denouement – represents a resoundingly successful, if somewhat extreme, example of Prudhomme’s philosophy, for this edition at least.

But… there’s always a but.

In defence of the long, boring Tour stage

I know I ain’t doing much,

But doing nothing means a lot to me

Ronald Belford Scott, Down Payment Blues (1978)

A.S.O., Pauline Ballet

Now, I know what you’re thinking. Arguing for more long, pan-flat, even boring sprinters’ stages during one of the most enthralling Tours de France in recent memory seems pretty strange and counterintuitive, right? Be careful what you wish for, and all that.

But bear with me for a moment.

In a purely sporting sense, throwing the peloton’s starving sprinters a bone would have added to, not lessened, the 2022 race’s spectacle and intrigue. Sprint finishes, and the riders who contest them, are an essential part of the Tour’s iconography – it would be hard to imagine the pre-Tour adverts on ITV and Eurosport without them – and often provide some of the race’s most emotional stories.

The opening weekend in Denmark, which so far accounts for two-thirds of the 2022 Tour’s bunch sprints, was dominated by the poignant symmetry of Fabio Jakobsen and Dylan Groenewegen’s comeback wins and the Dutch pair’s fractured shared history since their horrific crash in Poland. Imagine if we had been able to continue pulling at that tantalising thread for at least a few more days during the opening week?

An emotional Dylan Groenewegen celebrates winning stage three of the 2022 Tour de France (A.S.O., Charly Lopez)

Two or three additional sprint stages would also have added a touch more suspense to the green jersey competition, which has been dominated this year by Van Aert, the pinnacle of the new sprinter-rouleur-climber hybrids infiltrating the sport, and one suited to the constant demands of the modern Tour. The Belgian Jumbo-Visma rider, by snatching a few points at the intermediate sprint, mathematically wrapped up the green jersey competition midway through stage 17 to Peyragudes. Though, in all honesty, the contest was sewn up long before then.

Ironically, as it’s hard to tell from the Tour’s parcours, we’re arguably in a golden age of top-drawer sprinters, from Groenewegen and Jakobsen to stage 15 winner Jasper Philipsen, Van Aert himself, and the frustrated Ewan, as well as the likes of non-starters Sam Bennett, Arnaud Démare and Mark Cavendish. These world-class cyclists, who on their day are still all capable of winning at the Tour, have nevertheless been forced to fight over breadcrumbs at their sport’s biggest event, if they were even selected at all.

As pro cycling enters a new age of world-beating all-rounders, shunning decades of increasing physiological specialism, the last of the true specialists are being left out in the cold.

Wout van Aert - the consummate all-rounder (A.S.O., Pauline Ballet)

Away from the racing considerations, the Tour de France is also, as we cycling fans love to keep telling ourselves, much more than a sporting event. The race is a history lesson, a geography class, an anthropology seminar and a language crash course. It teaches you about the land the peloton passes through, and the people who inhabit it. Flat stages, with their long, long stretches of tactical nothingness, allow us to soak in all the Tour’s other cultural and scenic charms, unhindered by anything as boorish as actual bike racing.

More than any other sporting competition, bar maybe the Olympics or the World Cup, the Tour can act as a companion for three weeks. As I noted earlier, my first real encounter with the race was back in 2003, when we had just moved into our new house. As we (I was still at primary school, so I use ‘we’ loosely here) put down the wooden floor in the living room, tiled the kitchen and bathroom and furnished the place, the Tour was always there in the background, ticking along, waiting for us to rush back in when someone attacked, or crashed, or won.

Sprint stages, as boring as they might seem when the Tour route is announced the autumn before, form an essential part of our relationship with the race. With a break established up the road, and the yellow jersey’s team setting the pace behind, they set a fairly standardised rhythm not only to the peloton’s day, but to our own – they allow us to work, cut the grass, put the washing on, read a book, go for a coffee, have a nap; all with one eye on the screen in case something exciting and unexpected happens.

(Although too many days along the lines of stage six at this year’s Giro d’Italia might even drive you to clean out the gutters.)

Unlike the dazzling, all-consuming affair of, say, a Premier League football match, the Tour’s relationship with its viewers is more akin to that of a decades-long marriage. Sometimes it’s fine to just sit and say nothing.

A.S.O., Pauline Ballet

But, alas, we’re in the TikTok generation now. Modern sports fans, so we’re told, have a limited attention span and demand action at all times, condensed and easy to digest on TV and – God forbid – social media. The need for constant excitement has been, paradoxically, heightened by the recent trend towards wall-to-wall coverage, and has ensured the demise of gentle six-hour traverses through La France profonde, with nothing but fields of sunflowers, tractors, chateaux, and the colourful haze of an ambling peloton to entertain. And the pure sprinters have suffered as a result.

While the anti-sprinter experiment has been successful this year, if the Tour continues in this vein, it won’t always produce the consistent attacking and excitement envisioned by the organisers, and something will be lost.

So, as you watch Tadej Pogačar and Jonas Vingegaard slug it out on the torrid slopes of the Hautacam this afternoon, spare a thought for Fabio Jakobsen, Caleb Ewan and the rest, hauling themselves over the Tour’s hardest climbs, all for that increasingly fleeting chance of glory.

And think, too, of all the chores you could have completed while waiting for just two or three more bunch kicks during the last three weeks.

After obtaining a PhD, lecturing, and hosting a history podcast at Queen’s University Belfast, Ryan joined road.cc in December 2021 and since then has kept the site’s readers and listeners informed and enthralled (well at least occasionally) on news, the live blog, and the road.cc Podcast. After boarding a wrong bus at the world championships and ruining a good pair of jeans at the cyclocross, he now serves as road.cc’s senior news writer. Before his foray into cycling journalism, he wallowed in the equally pitiless world of academia, where he wrote a book about Victorian politics and droned on about cycling and bikes to classes of bored students (while taking every chance he could get to talk about cycling in print or on the radio). He can be found riding his bike very slowly around the narrow, scenic country lanes of Co. Down.

Latest Comments

- Rendel Harris 6 min 22 sec ago

But we could have ANPR cameras automatically issuing sanctions to vehicles over a certain width who ignore posted restrictions, no physical...

- Rendel Harris 29 min 35 sec ago

I'd say as a rough estimate of drivers who deliberately behave badly towards me when I'm cycling it would be split 90/10 male/female, of those who...

- Tom_77 1 hour 26 min ago

The SaddlePod looks nice, but if you're in the UK by the time you've paid shipping ($31) and import duty (who knows where we'll be with that come...

- TheBillder 1 hour 29 min ago

I've had (past tense is deliberate) 3 of these over the past 5 years. I'm back here researching for a replacement as my last one broke last week. I...

- chrisonabike 3 hours 31 min ago

And the next time - plead sympathy for your addiction, caused by trauma from your previous "accident"...

- wtjs 3 hours 34 min ago

Butyric Acid... was the most disgusting thing I have ever smelt in the lab...

- ubercurmudgeon 4 hours 5 min ago

Even a stopped clock, etc, etc...

- Bigtwin 5 hours 26 min ago

I wouldn't be meeting that Orange Pillock anywhere, let alone 1/2 way.

Add new comment

4 comments

I love this article, but have less sympathy for the sprinters.

Cav said sprinters would find 2022 hard but most agreed pre-race that Stages 2, 3, 4, 13, 15, 19 were all opportunities for sprinters. Based on your stats, 2021 wasn't much friendlier for sprinters yet Cav sweeped up 4 wins.

I'd say the Tour has far fewer opportunities for breakaway riders, and that is bad news for all but the Top 2-3 teams, which rely on these stages for any chance at glory. The only reason so many breakaways succeeded in 2022, is because the riders committed so incredibly hard this year in a thrilling TdF.

Given the entertainment we've had with the epic GC battle being so visible on the road this year, I'd take that risk. Because we had lost something else in recent years - the breakaway that stayed out and won.

I don't miss the "doomed breakaway - go off for a 3 hour snooze - sprinters teams on the front - inevitable well timed catch enabled by race radio - 2 minutes of action" charade. We might not get this year's drama again if we don't have covid decimating teams, WvA doing his thing, Pogacar attacking like that, etc, but I'm pretty happy with the balance now and probably TV and sponsors are too.

Jakobsen's battle to meet the time cut yesterday was a story in itself.

If there is a French rider that is the best sprinter in the world there will be a few more sprint stages.

The first week should be a series of one day spring classics type races. Bit of rolling countryside, with some days with short, sharp climbs, cobbles, strade bianche etc thrown in for giggles. Alternative days for bunch sprints, but with the possibilities of breakaways and classics specialists, and the risks of a GC contender breaking their collarbone on the cobbles.