- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

Swiss Side Wind Tunnel 27.jpg

Swiss Side Wind Tunnel 27.jpgRolling resistance: why you need to choose your tyres carefully if you want to ride faster

If you want to cycle faster – or ride at a given speed for less effort – you need to choose your tyres carefully and set them up right to minimise rolling resistance.

We spoke to Jan-Niklas Jünger, bicycle tyre product manager at Continental, who gave us valuable and at times unexpected advice for increasing speed, maintaining grip while reducing rolling resistance, and also some interesting fuel for the tubeless versus tubular tyre debate. Oh, and if you’ve ever wondered how much difference changing your tyres can really make out on the road, he explained how to quantify it.

This article was originally going to involve talking with multiple bike industry figures, but Jan gave us a huge amount of information that we didn’t want to waste so we’ve decided to run it as an extended interview. Not surprisingly, that means there are lots of references to Continental products, but it’s not an ad for the German brand. As the BBC would say, other brands are available.

Right, let’s get cracking. We’ll start at the very beginning…

What is rolling resistance?

Rolling resistance is one of the forces that opposes you as you ride forward, the main reason for it being that the tyre is constantly deforming as you move (here we’re dealing with rolling resistance as it relates to your tyres; we’re not looking at things like bearing friction). Not all of the energy used to deform the tyre is recovered when the pressure is removed.

“Rolling resistance is energy change,” says Jan. “You push the pedals and this results in speed, while aerodynamic drag and rolling resistance are holding you back.

“Material deforms in contact with the ground, molecules rub against one another creating heat that goes into the environment. That’s where you are losing energy in what we call rolling resistance.”

How important is rolling resistance?

From about 20 km/h (12.5 mph) upwards, aerodynamic drag is the largest force working against you as you pedal – and Dave looked at it in detail when he visited the wind tunnel – with rolling resistance coming in as runner-up.

> Why riders like you need to get more aero and wheel weight doesn't matter

“Aerodynamic drag grows exponentially with speed,” says Jan. “It will vary depending on the tyre, pressure, tarmac and so on, but at typical road bike speeds aerodynamic drag might account for 70% of the effect holding you back, with about 20% down to rolling resistance. All other factors – like your chain rubbing, the bearings – might be only 10%. If you’re a performance-orientated cyclist, rolling resistance is something that you should take a look at because there’s a lot to gain.

“The energy lost in rolling resistance is linear. The faster you go the larger it gets, so if you are doing 50 km/h (30 mph) in a time trial the energy loss is higher than if you were commuting or going up a hill.”

Less energy lost means greater speed or the opportunity to move at the same speed as other riders more easily.

“If you could reduce rolling resistance in your tyre by 10% when going up a hill, you could take another bottle of water with you, for example,” says Jan. “The typical rolling resistance of a decent tubular setup at 20 km/h (12.5 mph) can result in 30 watts, so 3 watts saved allows you to take another 500g more weight on a gradient of about 5-7%. That’s a reason why pros are looking at the tyres they use for a race or stage.”

Tyre type and size is important

“The more material that deforms, the bigger the rolling resistance,” says Jan. “So a big, knobbly tyre or a tyre with a thick tread will give greater rolling resistance than a 25mm road tyre, and a thick butyl inner tube will add rolling resistance.”

Things get more complicated when it comes to choosing between narrow tyres and wide tyres.

Tyre width has become a hot topic in the road world over the past few years with 25mm tyres now much more popular that 23s in competition, and some racers going even wider.

Inflated to the same pressure, a narrow tyre and a wide tyre have the same contact area, but the shape of the contact patch is very different. A narrow tyre has a long and slim contact patch, a wide tyre has a short and broad contact patch.

The longer flattened area of a narrow tyre means the wheel loses more of its roundness as you move along, producing more deformation during rotation.

In comparison, the length of the flattened area is shorter with a wider tyre, so the tyre is rounder and it rolls quicker.

Of course, you’re likely to inflate a wide tyre to a lower pressure than a narrow one. This will enlarge the contact area and increase the rolling resistance. However, according to figures from Continental, you can run a 25mm tyre at 94psi and it’ll have the same rolling resistance as a 23mm tyre at 123psi. A 28mm tyre inflated to 80psi will have an equal amount of rolling resistance.

Speaking of pressure…

You need to get your tyre pressure right

If the deforming of your tyres leads to increased rolling resistance, you simply need to pump your tyres up rock hard and wait for the Strava KOMs to roll in, right?

It’s never as easy as that, is it? Ride on the smooth boards of the velodrome and, yeah, you can pump your tyres up to maybe 8-12 bar (116-174psi), but everywhere else you need to consider the surface you’re riding on.

“Off road it’s important that you connect to the ground – that the spring effect of the tyre is not pushing you upwards and that you’re not jumping up and down,” says Jan. “So off road it’s faster if you have lower pressure to help you stick to the ground.”

You might choose a tubeless 32mm tyre at 3 bar (44psi) for the Paris-Roubaix cobbles, but that’s hardly an everyday situation for most of us.

“If you go to the road it’s quite different,” says Jan. “It depends on how rough the road surface is where you are going. You need to choose the tyre pressure based on the tarmac structure.

“Riders should start to experiment dropping their pressure in a road tubeless tyre; 6 bar (87psi) for a 25mm tyre should be the maximum. Above that, we see in our measurements that there is a dead spot where rolling resistance in perfect real world conditions on super smooth roads doesn’t get any better.

“There are some nice apps people can play around with, and pressure sensors from the likes of Quarq and SKS.”

The tyre carcass makes a difference

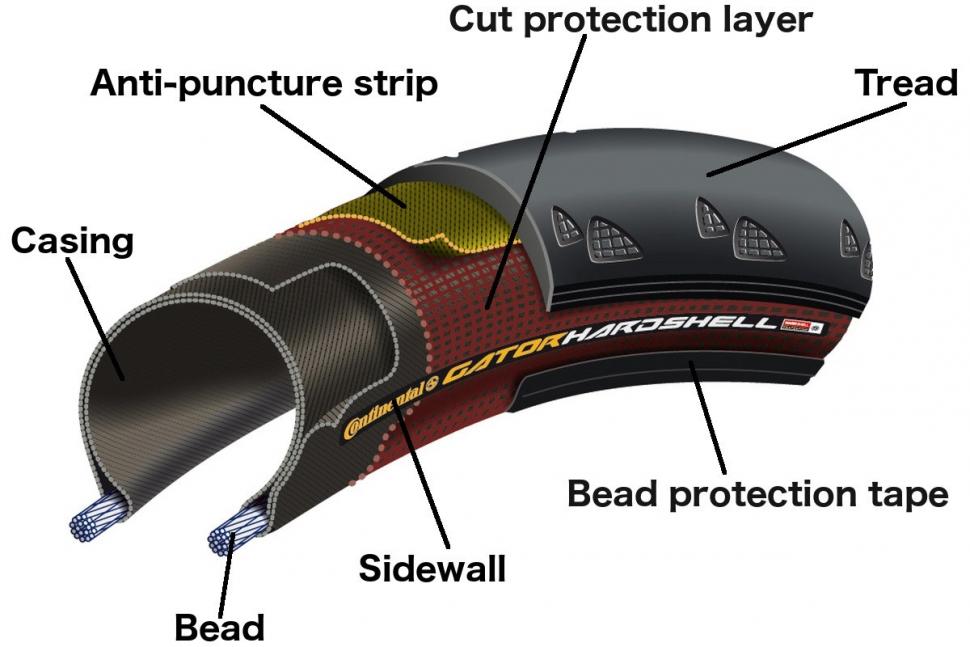

The carcass – or casing – is essentially the skeleton of the tyre, and it can be made of various materials.

“At Continental we have a polyamide carcass in different TPI (threads per inch) numbers.” says Jan. “The higher you go with the TPI the lighter the tyre gets because the thickness of the carcass material goes down. You can have a very cheap mountain bike tyre at 27 TPI with a thick carcass material. We go to a TPI of up to 200 and the diameter of the fibre gets smaller.

“The material is normally folded over three times in a traditional tyre setup and there are different patents out there on how you fold over the carcass, if you have a triple layer in the middle, or if you have other folding techniques.

“As the diameter of the fibre gets smaller the rubber you need to put over, under and between the threads is less – so the higher the TPI count the less material is put in it and the lighter the tyre gets. But a higher TPI does not always lead to better rolling resistance. A tyre can only be faster when a high TPI is combined with a very thin liner of the correct rubber compound.”

Manufacturers choose different rubber compounds for the carcass depending on the intended use of the tyre.

“In downhill mountain bike tyres you would like to have the best damping so the type of rubber would be different to what you would put in to a time trial tyre or a GatorSkin [which is built for strength and durability], for example,” says Jan.

A puncture breaker can affect rolling resistance

Manufacturers often put a puncture breaker – or a puncture protection layer – between the carcass and the tread, and this can affect rolling resistance.

“There’s a lot of difference depending on the type of breaker you put in,” says Jan. “The puncture breaker can be the difference between a premium bike tyre and a standard bike tyre.

“For example, a nice feature of our patented Vectran breaker is that it doesn’t influence the rolling resistance. But an entry-level puncture breaker or a polyamide material will increase the overall rolling resistance.”

Sticking with the Continental range, the SuperSport Plus tyres, designed for “messengers, hardcore commuters and fixie riders”, are made with with thick casing rubber for a high level of sidewall durability, and a Plus breaker belt that’s described as “a thick elastomer layer beneath the tread to provide superior puncture protection”. The flip side is that these tyres aren’t particularly fast compared with others in the line-up.

The GrandSport tyres use a nylon NyTech breaker while GatorSkins have a PolyX breaker made from a densely woven polyester fibre that’s said not to have a negative effect on rolling resistance.

You can’t have it all when it comes to the tread

Not surprisingly, the tread – the rubber that connects you to the road – plays a big role in determining a tyre’s overall performance, including its speed.

“There are three major factors you have to consider in the tread: mileage, grip, and rolling resistance,” says Jan. “If you better one characteristic, you change the other two.

“If you want to have the fastest tyre with the fastest rubber compound in the world you can be sure that it will have no grip in corners or in the wet! If you want to have the tyre that best sticks to the road you can be sure that it will be slow and that it will rub away like a pencil eraser.”

Manufacturers spend a lot of time developing the rubber compounds that give them the characteristics they want for a given use. The best compound for a winter training tyre – where durability and wet-weather grip are most important – isn’t the same as for a time trial tyre – where low rolling resistance is the priority.

“You can have a single tread compound or you can have the fastest rubber in the middle of the tread and stickier rubber on the shoulder,” says Jan.

What should you look for in a rubber compound if you want a low rolling resistance? It’s not easy to answer that question, partly because tyre manufacturers guard the information about precisely what ingredients they include in their mix.

“Over 100 different raw materials might go into a rubber compound, and the details of what we use I can’t tell you.” says Jan.

“The good thing about carbon in its molecular structure is that it offers most contact points to other molecules,” says Jan. “But when you use carbon you can mostly only go towards one characteristic, be it mileage, grip or rolling resistance.

“Modern rubber compounds aren’t just carbon-based they’re more like active silica-based. In the 1980s or 1990s bicycle tyres could only offer one characteristic in a tyre, so you needed one tyre for training, one tyre for normal racing and one tyre for time trialing. With active silica you can control the characteristics better so a compound might not just be best in one class.

“This is caused by the typical energy losses of silica molecules at different vibration frequencies. Up to 100 km/h (62.5 mph) – which would be about 27 m/s or about 13 revolutions of a 28in wheel per second (the frequency of the tyre deforming is 13 Hertz – energy losses at low frequencies are low for best rolling resistance, whereas at high frequencies the energy losses are high and help you to have good grip.”

In terms of tread pattern, a smooth tyre has the least rolling resistance, all other things being equal. A knobbly tyre has a higher rolling resistance because the knobs can deform relatively easily, creating heat – and you know how slow mountain bike tyres can feel on the road.

“Even on a small scale, if we have a slick tubular and a fine diamond-pattern tubular, we see a zero-point-something watts difference in rolling resistance, and this is important for our professional teams like Ineos,” says Jan. “The slick tyre is measurably faster than a non-slick tyre, and that’s the reason why all track cycling tyres are slick.”

There’s usually a compromise when it comes to choice of inner tubes

Inner tubes, if you use a system that requires them, are similar to tyres in that a single option can’t offer the best of all worlds.

“You have different materials – butyl in thick, thin, and super-thin – latex, TPU [thermoplastic polyurethane] and more materials coming up,” says Jan. “Latex is more or less neutral in terms of rolling resistance and thin latex is quite good. The problems with latex are that you have to keep it away from oil, you must be careful not to cut it, and you lose air over 24 hours so you have to re-pump it a lot, but for rolling resistance it’s the best inner tube.”

AeroCoach’s comparative testing of inner tubes last year found that a latex tube might offer a 7 watt saving over a regular butyl inner tube (testing was carried out using a Continental GP 5000 25mm tyre at 90psi and 45 km/h).

TPU is a relative newcomer on the scene. We’ve reviewed super-light TPU inner tubes from Tubolito (38g, for 18-28mm 700C tyres), for example, on road.cc. TPU can offer a low rolling resistance but it’s not all good news.

“I don’t think that TPU tubes have yet reached the full capability of the material,” says Jan-Nilklas. “A lot of people have problems with their TPU tube, some probably resulting from misuse from the customer’s side but also maybe some products are not yet fully developed.”

If you go tubeless, add your sealant carefully

You don’t need an inner tube at all with tubeless tyres (which you run on specific wheel rims) but you do need to add liquid sealant if you want the benefit of puncture protection (the sealant solidifies to plug the hole).

> Find out if tubeless tyres are the best option for you

“Obviously, the more sealant you put into a tyre the higher the rolling resistance will be, as you know if your friends have ever played a trick on you and put water in your tyre,” says Jan.

“The amount of sealant is very important. You shouldn’t put no sealant in because you’ll have no puncture resistance, but more than 50 ml of sealant in a road tyre will slow you down a little bit and it’ll even you out with an inner tube setup again.

“If you run a fast gravel tyre with some knobs as a tubeless setup, it can be faster than a slick training all-round tyre with a butyl inner tube in it. Our Terra Speed tubeless gravel tyre is even with a GP 4000 fitted with a traditional inner tube which you would have used five years ago.”

> Read our review of the Continental Terra Speed

Tubulars no longer offer the lowest rolling resistance

A tubular tyre – or a tub – which again requires a specific rim, consists of the carcass material, the rubber, the inner tube, the base tape and the stitching. You also need to factor in the glue or tape that’s used to stick the tub to the wheel.

“All of this material can deform and there’s a 5 watt difference at 30 km/h (19 mph) between a tubular and a Continental GP 5000 with a latex tube or a tubeless setup,” says Jan. “This is why you see even national track teams for the Olympics changing to clincher setups.”

Changing a single tyre can make a significant difference

As you’ll doubtless know, your weight isn’t distributed evenly across the two wheels when you sit on your bike; the rear wheel takes the majority of the load. That means the rear tyre deforms more than the front wheel, so it is responsible for the majority of the rolling resistance. That figures, right?

“Typically 70% of the rolling resistance comes from your rear wheel and 30% from your front wheel,” says Jan. “Normally people change both of their tyres together, but the biggest change to rolling resistance is in the rear.

“If you want to better your rolling resistance and not lose grip in corners, you could change to a faster tyre at the rear and stay with a very grippy tyre at the front.”

You can work out the gains of switching tyres, but you’ll need some specific info

You can work out how much you stand to gain by switching tyres, but you’ll need to know the Crr – the coefficient of rolling resistance – of the relevant tyre first.

“Your rolling resistance losses (in watts) are your Crr multiplied by your system weight multiplied by your speed multiplied by gravity,” says Jan.

Rolling resistance losses = Crr x system mass x speed x gravity

Your system mass is you, plus your bike, plus everything you’re wearing (in kg) – so before going for a ride you could take your bathroom scales outside and stand on them while holding your bike off the floor.

Your speed is in metres per second.

Gravity has a conventional standard value of approximately 9.81 m/s2.

The Crr is more tricky! Determining this requires specialist equipment (usually), but you can go to www.bicyclerollingresistance.com – which is independent of any tyre brand – and get info on key tyres (a lot of which requires a subscription, but it’s not expensive).

Suppose that your system weight is 85 kg, your speed is 36 km/h (10 m/sec), and that you look up Tyre A and find that its Crr at 80psi is 0.005.

Your rolling resistance losses would be:

0.005 (Crr) x 85 (mass) x 10 (speed) x 9.81 (gravity) = 41.7 watts

This loss would be across both tyres combined.

Now suppose that you keep everything else the same but swap to tyres with a Crr at 80psi of 0.004.

0.004 (Crr) x 85 (mass) x 10 (speed) x 9.81 (gravity) = 36.7 watts

By swapping from Tyre A to Tyre B you’d save 5 watts (41.7 watts minus 36.7 watts). In other words, you can achieve that same speed of 36 km/h while putting out 5 watts less power.

Further reading

This article is designed to introduce the concept of rolling resistance and explain the basics. If you want to know more, we’d suggest taking a look at www.bicyclerollingresistance.com. It’s an excellent website if you want to geek out.

We know you’re internet savvy but if you want to go old school the book Bicycling Science by David Gordon Wilson has an excellent section on rolling resistance: tyres and bearings.

Mat has been in cycling media since 1996, on titles including BikeRadar, Total Bike, Total Mountain Bike, What Mountain Bike and Mountain Biking UK, and he has been editor of 220 Triathlon and Cycling Plus. Mat has been road.cc technical editor for over a decade, testing bikes, fettling the latest kit, and trying out the most up-to-the-minute clothing. He has won his category in Ironman UK 70.3 and finished on the podium in both marathons he has run. Mat is a Cambridge graduate who did a post-grad in magazine journalism, and he is a winner of the Cycling Media Award for Specialist Online Writer. Now over 50, he's riding road and gravel bikes most days for fun and fitness rather than training for competitions.

Latest Comments

- Dnnnnnn 3 hours 10 min ago

You're too kind. They just seem to be unpleasant trolls.

- ktache 3 hours 51 min ago

I realised that the lads crash is a rare set of circumstances, and the numbers in the race would add complexity, but don't smart watches have...

- Jogle 4 hours 5 min ago

And in Southampton today we had another example of those entitled ambulances going through red lights without a care for anyone else!...

- belugabob 5 hours 16 min ago

Because the number of 40% tax payers buying downhill bikes on the scheme, whilst lower rate tax payers (who are more likely to actually cycle to...

- TheBillder 5 hours 19 min ago

The spokes and nipples are not anodised for environmental reasons, but the rims are. Which is a lot more metal. Hmm...

- Zebulebu 5 hours 52 min ago

Yeah, they'll be great after being crushed in your jersey pocket for three hours. ...

- Rendel Harris 5 hours 58 min ago

I'm afraid so, anything operated by TfL apart from the Woolwich ferry and the Silvertown Tunnel bike bus when it opens next month.

- Backladder 7 hours 6 min ago

Its only "meh" because we all experience similar passes every ride, I'm sure if they got their finger out and worked out the distance it would be...

- Global Nomad 7 hours 7 min ago

have (had) both generations of Empire and loved their fit, so hoping the update keeps the same shape/last. Hope they're going to have a good range...

Add new comment

8 comments

Jan Heine at Rene Herse Cycles has done a lot of tyre testing over the years in real world conditions. A number of blog posts there make for very interesting reading.

He's even produced a handy tyre pressure calculator at https://www.renehersecycles.com/tire-pressure-calculator/ .

In my experience lowering tyre pressure may increase resistance but it is outweighted by a more comfortable ride which seems to equate to increased speed, like the proponents of larger tyres espouse.

It may just be that lower tyres pressures equate to conserving energy by being less beaten up on our crap roads.

They do.

Ride comfort has often been an under-appreciated factor when recommending tyre pressures. Too high a pressure not only causes discomfort but also will increase fatigue from vibration while the constant tyre deflection will also slow you down on anything but super-smooth asphalt.

This is very detailed but you can get a good idea from just the charts:

https://blog.silca.cc/part-4b-rolling-resistance-and-impedance

As with having a puncture belt under the tread, a tyre with stiffer sidewalls will be more rigid than thinner, more pliable ones so will transmit more vibration from the road surface, even if you reduce the air pressure further.

Well written article, Matt. Thank you for going deeper into the subject matter than some of the other articles on road.cc.

One question regarding TPU tubes, you state "but it’s not all good news". Can you elaborate on this? Do Schwalbe’s new Aerothan tubes also suffer from the same negatives?

As a fan of them, I wish that Continental made a file tread tubeless road tyre; on the rural roads were I ride, the usual 'winter' tyres aren't really up to it. A 28-32mm tyre would do just nicely.

Funnily enough I avoid using file tread tyres in the winter. Where I ride there's a lot of flints and I find a file tread collects them and allows them to work their way into the tyre causing a puncture.

I used 32mm Gravelkings briefly last winter and had three seperate punctures on one ride and two on another. They went in the bin after that.

A fascinating read Matt so thanks for your excellent feature. As you know, John Lafford and I did a lot of tyre testing using John's rig and his tru engineering calcs that gave a Crr for each tyre - and this was back in the 90s.

One thing we noticed was that some tyres, Michelin for instance, hit a ceiling when it came to tyre pressure as their carcass inflated to a point and then blanked any further increase in pressure. So, in Micjelin's case, pushing pressures above 100psi was fruitless and their tyres felt like lead if 'over-inflated'. However, and a good point to mention to Jan-Niklas, was that Conti's appeared to benefit from over-inflation as they swelled so the 'light bulb' shape/effect of a super-squishy tyre above the rigid rim kept going above 100psi up to 125+. This was because the tyre increased in volume - something that the broad cycling world has now acknowledged!!!

? Ah.

Think I may just go for cycle and give that some thought.