- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Tubeless valves

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

Why am I putting out more power on the hills than on flat roads? We speak to a bike fit expert and hit the indoor trainer to find out

This article includes paid promotion on behalf of Rouvy

Have you ever noticed that your legs seem to have a little extra magic on the climbs, but end up feeling like lead on the flats? Don’t worry, you’re not alone. Bike fit guru Phil Burt and our own Jamie Williams sat down for a chat to uncover some fascinating insights about biomechanics, resistance, and the unique quirks that make every rider different.

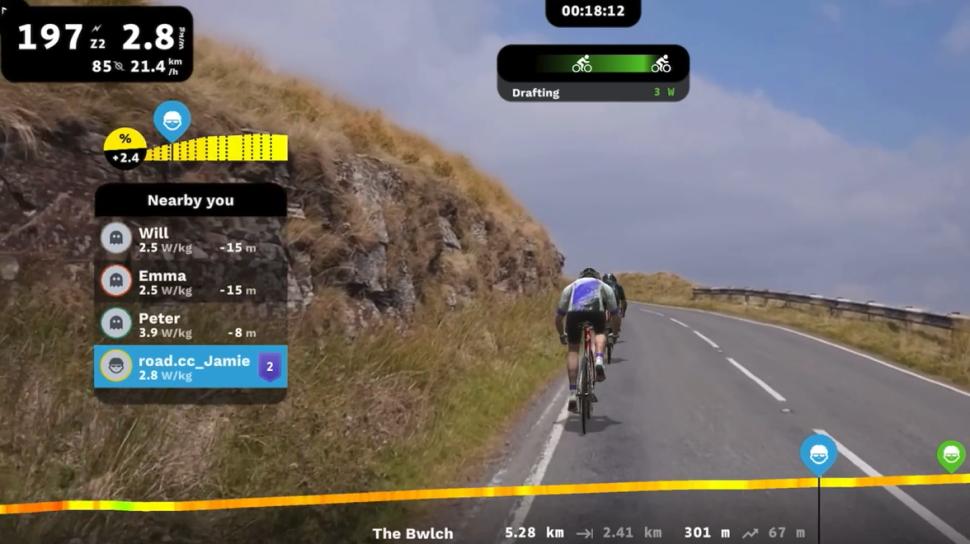

Not very long ago, Rouvy got in touch and asked us if we could make a video showcasing some of their 1,500 augmented reality routes. They said there’s flats, there’s climbs, there’s descents and there’s even gravel, but when Jamie started going down some of the virtual routes, he realised something rather interesting — he could sustain way more power when riding up a climb than he could on the flats.

On a seemingly endless flat road in Iceland, maintaining a 200-watt output on the bike had Jamie already building up a sweat. But when we put him on a climb — one of Rouvy’s latest Columbia routes — 200 watts suddenly seemed a whole lot easier for him.

And it wasn’t just a one-off. We tried many other virtual roads on Rouvy, like the ones in Madagascar, the Dolomites, Death Valley, Yokohama, or even the local climbs around Bath and Bristol, the result was always the same — more power on the hills than on the flats.

How can that be? We called leading physiotherapist and bike-fit boffin Phil Burt to find out the answers…

Biomechanics and positional changes

Phil Burt was the lead physiotherapist at British Cycling for 12 years and consultant physiotherapist for Team Sky for five years. He now has his own bike fit and physiotherapy practice, Phil Burt Innovation, which has brought him into contact with hundreds of ordinary riders like us, as well as the elite cyclists he used to look after.

According to him, the primary factor at play is the subtle change in body position when cycling uphill. The raised front end of the bike alters how muscles engage, potentially creating a more efficient power transfer.

“What quite often will happen is that people lean into the pedal stroke a little bit more,” Burt explains. “So if you can imagine on the downstroke, because the front end’s coming up slightly higher, you might sit slightly further back and push in a closed ankle position at the bottom. That might be producing a more efficient way of transferring power.”

When climbing, cyclists will often lean into the pedal stroke with a closed ankle position. This engages the glutes and quads more effectively, which are the primary power generators in cycling. For some, like Jamie, this bio-mechanical adjustment optimises muscle coordination and output.

However conversely, for others, climbing may close the hip angle too much, leading to a loss of power. Burt notes: “Some people complain about not being able to maintain a big cadence going uphill because they start to have a big dead spot at the top of the cycling profile as the hip’s closing up.

“But I think with you — and others like you — it might be more optimal to be in that slightly backward position… when you go uphill, it lets you lock out your ankle in a more efficient way.”

Resistance and muscle engagement

Increased resistance on a climb might also play a role. Burt likens climbing to performing a heavy squat: it requires maximal effort, activating more muscle fibres and accessory muscles for stabilisation.

“When we go uphill, you have to push this resistance to continue moving forward,” he says. “What we do know is that you fire up more muscles when the challenge is harder, and potentially you are firing up more of your muscles in a more coordinated way.”

On the flats, lower resistance may fail to fully engage these muscles, limiting power output. As Burt explains: “It’s like being on a really leg-heavy leg press machine with no weight on it. It’s very hard to engage your musculature effectively.”

So how to mimic that same effect on the flat? Well, go out and put on a bigger chainring or simply use higher gears.

So… what does all this mean for you?

Of course, no two riders are the same. Burt points out that individual biomechanics ultimately dictate how each cyclist generates and maintains their power. “We all achieve the task of pedalling in slightly different ways,” he says. Factors such as ankle flexibility, hip mobility, and even personal bike fit “windows” influence performance differences.

So, should you adjust your bike setup for specific terrains? Burt advises caution. While a specialised setup might boost performance for climbs or flats, it could compromise overall efficiency. “In Tour de France, if it’s a time trial and it’s slightly uphill, sometimes they’ll change bikes,” he says. “But for a regular stage, the position reflects the best compromise for going uphill, downhill, and on the flat. It’s probably not optimal for any one of those, but it’s the best fit overall.”

For those wanting to improve their weaknesses, Burt recommends focused training. Those who enjoy flat terrains could incorporate heavier resistance intervals to stimulate climbing muscle engagement, while climbers might choose to work on cadence and power consistency on the flats.

However, there can be pitfalls in obsessing over small differences like these, he says, noting that slight asymmetries and terrain-based strengths are natural. “Hardly anybody in the world has perfectly symmetrical power left and right. Trying to make them the same can often bring the overall power down,” Burt adds.

So whether you’re powering up climbs or cruising on flats, the key lies in understanding your unique biomechanics, focusing on your bike position and optimising your training. And if you think you’re stronger on the flats or the climbs, there’s a variety of reasons for it, but it’s probably not worth stressing about. If you want to be stronger everywhere, then there's one proven way to do it: a bit of good old-fashioned training!

Head over to Rouvy for a free trial if you aren't already signed up.

Latest Comments

- Nick T 27 min 47 sec ago

If he's not charging VAT yet then it would appear he's making well under 25 bikes per year currently. 8 full builds at 10-15k would send you over...

- ktache 44 min 9 sec ago

That looks like a fun bike. Frame only, 2 and an 1/2 grand.

- Robert Hardy 59 min 59 sec ago

But down the line it can put a big dent in its resale value which ups leasing costs and the amount of cash an owner is throwing at their status...

- ktache 1 hour 16 min ago

Only reading the headline on the homepage, not the rest of the article, but I only ride mountain bikes and I still get close passed...

- wtjs 1 hour 40 min ago

Fair enough, personal experience may trump (not that one) theory. However, the bonking I have experienced has been due to lack of carbs. Your point...

- wtjs 1 hour 53 min ago

Agreed, but he was still right to publicise the event. The police, if they're anything like Lancashire, will do nothing at all.

- Rendel Harris 3 hours 7 min ago

mdavidfrodo?

- wtjs 6 hours 47 min ago

in the UK we have policing which to a greater or lesser extent relies on assistance from members of the public......

- Cadcam 7 hours 51 min ago

Just wanted to share a quick thank you to everyone who helped out in this thread....

Add new comment

7 comments

That'll be why climbers have such bigger quads than TT specialists and sprinters then.

What's a "closed ankle position?"

A Victorian attitude to dress?

I was wondering exactly the same, sometimes text really needs an image to get the description across.

In the same way a closed hip angle is the reduction in the angle between the torso and upper leg at the hip, I reckon it means a reduction in the angle between the lower leg and foot at the ankle joint. I'm picturing it as pedalling with the toes down opens the angle and heel down closes the angle.

So hang on, if I use a bigger gear at the same rpm I will put out more power? No, you've lost me, this is getting too technical…

I think they're making an assumption here that a rider can apply more force required for a bigger gear at the same cadence.

Power (W) = Force (N) x Cadence (rpm) , power only goes up if either force or cadence goes up

power (M1L2T-3) = torque (M1L2T-2) x cadence (T-1) = force (M1L1T-2) x crank length (L1) x cadence (T-1)