- News

- Reviews

- Bikes

- Accessories

- Accessories - misc

- Computer mounts

- Bags

- Bar ends

- Bike bags & cases

- Bottle cages

- Bottles

- Cameras

- Car racks

- Child seats

- Computers

- Glasses

- GPS units

- Helmets

- Lights - front

- Lights - rear

- Lights - sets

- Locks

- Mirrors

- Mudguards

- Racks

- Pumps & CO2 inflators

- Puncture kits

- Reflectives

- Smart watches

- Stands and racks

- Trailers

- Clothing

- Components

- Bar tape & grips

- Bottom brackets

- Brake & gear cables

- Brake & STI levers

- Brake pads & spares

- Brakes

- Cassettes & freewheels

- Chains

- Chainsets & chainrings

- Derailleurs - front

- Derailleurs - rear

- Forks

- Gear levers & shifters

- Groupsets

- Handlebars & extensions

- Headsets

- Hubs

- Inner tubes

- Pedals

- Quick releases & skewers

- Saddles

- Seatposts

- Stems

- Wheels

- Tyres

- Health, fitness and nutrition

- Tools and workshop

- Miscellaneous

- Buyers Guides

- Features

- Forum

- Recommends

- Podcast

Velocio sustainability fabric rolls

Velocio sustainability fabric rollsHow environmentally sustainable is your cycle clothing?

It’s very encouraging to see a rise in eco-labelled cycle clothing and with such great choice it’s no longer about do I pick something because it’s sustainable or do I need that other product because of its performance benefits—the two are not mutually exclusive. But with so many products claiming to be environmentally friendly, how far are the brands truly going reducing its impact? What is the greenest choice you can make?

We spoke to some of the cycle clothing brands leading the charge in sustainable practices, Rapha, MAAP and Velocio, to understand the decisions they’ve made, and based on this we’ve put together a guide on what you should look out for to make the greenest choice.

“We need to ensure we’re not just talking about what products are made from and switching to recycled materials because that’s low hanging fruit, but about how they’re made and then how they’re sold, maintained by the customer and dealt with at the end of their useful life as well,” Rapha’s Sustainability Manager Duncan Coulter believes, “you can think of it as like a timeline.”

MAAP’s Vice President of Product, Darren Tabone says it’s a way of working. “You’ve really got to be diligent in making sure that first of all you think about the environment and not the bottom dollar.

“We’d rather pay a little bit more to get the right material that, A, is sustainable but, B, makes our products superior, we’re also looking at it from a technical aspect with four-way fabrications and wicking technology.”

CEO and co-founder of Velocio, Brad Sheehan, adds: “Sustainability is a commitment and often requires a thoughtful approach and often ends up being the more costly (financially) direction—however, it’s a necessary investment into our greater future.

“We need to shift the perspective from easy/convenient/cheap towards thoughtful/quality/investment to ensure we have a better future.”

Breaking this down, continue reading to find out what you should be looking for in a product to check it is really environmentally sustainable over its entire lifespan.

Where are the greatest environmental impacts?

Before going into what to look out for in a product, here’s how brands can determine how to produce environmentally sustainable cycle clothing.

Completing a lifecycle assessment of a product can give an idea of what are its biggest environmental impacts from raw materials to the finished product, and therefore it can highlight the areas that the brand should focus on to make a difference. Rapha has done this for a lot of its products using the Higg Index.

“By plugging in all the materials used and all the processes that go into making the final version, you can find out the environmental impact for any given product,” explains Duncan of Rapha.

“You’ll know how much carbon and water has gone into it, how much it contributed to eutrophication in the area it was built, how much fossil fuels went into creating it, and a chemistry score as well.

“You’re able to start to understand where those impacts are and what types of impacts.”

It can also provide insights to the brand that they might not have been quite expecting. “Some environmental aspects of sustainability are quite counterintuitive,” Duncan admits and gives the example that you’d expect natural fibres like cotton and wool to have the lowest impact and synthetics and nylons made from oil should have the worst impacts, but it’s actually the other way around.

“It shows the way that the world is built around the petrochemical supply chain and because of that, the efficiencies that come out of it means things which should be bad for the environment we don’t notice how bad they are because we’ve maximised the efficiency to a ridiculous extent,” he explains.

Looking at the lifecycle assessment of a product, Duncan points out that around 80% of its impact comes from the material. “From the raw processing of that material, getting it out of the ground and turning it into pellets or into a yarn, and then turning that yarn into a fabric, and then turning that fabric into something that’s nice to wear against the body—all of that embodied energy is where all the impact is basically.”

Next up, the assembly phase—and what brands call tier one manufacturing—is where you get the rolls of fabric, cut it out and stitch it all together. “The only energy you’re really using there is when the lights are on, for the sewing machines and some cutting machines,” Duncan notes, not as much energy is used.

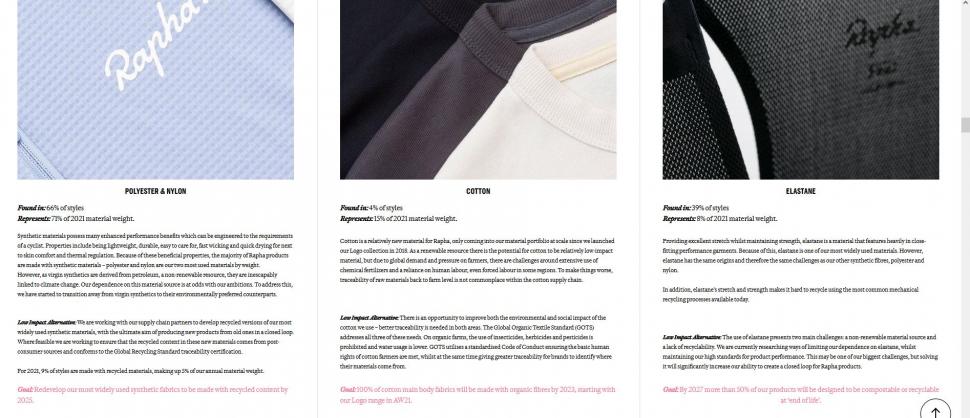

What is it made from?

In acknowledging the biggest impacts are with the raw materials, that’s where Rapha says it is focusing its energy. “One of the most ambitious impact figures we launched in March this year was for 90% of our production volume, not percentage of styles, to use what we deem as environmentally preferred materials by 2025 to particularly address the raw material phase.

“It’s harder doing it by volume because we have products such as helmets, shoes, pumps and water bottles that don’t actually have any solutions,” Duncan of Rapha admits.

It’s about stepping away from virgin synthetics to recycled synthetics, from conventional cotton to organic cotton, and from non-animal welfare materials to animal welfare standard materials.

Brad of Velocio says: “Polyester made of recycled plastic bottles or nylon from fishing nets, for example, both are used throughout our line and have the same level of quality and longevity, but do not tap further into resources to create virgin materials.

“Natural fibres or biodegradable fibres are also in the mix—there are noticeable benefits to these fibres in terms of comfort and performance, with the added benefit of being more sustainable.”

Is the brand being transparent?

“Information is key, we’re being transparent on our website about our journey,” Darren of MAAP points out.

Journey is the key word here, can you see details of progress made on the brand’s website? It’s not an overnight thing, so seeing the steps the brand has taken over time can be an indication that they’re being honest about the stage they are at.

Here are some examples:

“I’d look at what that brand has done in the past and is doing currently -- actually doing, not saying they’re 'looking into it' -- and base it on that,” Brad recommends. “Oftentimes, past performance is indicative of what’s important to a company.”

Darren of MAAP agrees, but admits it’s a two-way street: "I think brands need to be more transparent on their websites and I think consumers need to be prepared do their research.”

Rapha recommends looking out for standards of material traceability. “Don’t just believe what’s said to you at face value,” Duncan stresses, “what are the assurances that are being provided on transparency and traceability of products, showing that it is what it says it is.”

There’s the Global Recycling Standard that Rapha’s polyester and nylon yarns are signed up to for example. “You should be aiming for post-consumer recycled content which means that it’s had a useful life and then it’s going back into the system.”

Then there’s the Global Organic Textile Standard for cotton and the same applies to animal derived materials with, for example, the sourcing of down meeting the Responsible Down Standard.

MAAP uses organic cotton and supports the Better Cotton Initiative that educates farmers in China, Pakistan and even in the US where a lot of cotton is grown on how they can minimise the usage of water and reduce the use of harmful chemicals.

“A lot of people don’t realise how much water is used, for example, growing cotton,” Darren of MAAP notes. “Water is a big part of our supply chain and that can be detrimental to our communities and the environment.”

Do you really need it?

“The single biggest impact is creating the garment, so purchasing products that you really need and that will last is the best approach,” says Brad of Velocio. “Buy fewer, nicer things.”

By delivering a high quality product with features that are genuinely useful to you, the product is more likely to get used and have a fulfilled life.

“When you’re looking for an environmentally friendly purchase, I’d first ask whether you need to make that purchase,” says Brad.

> Review: Velocio Women's Ultralight Bib Short

By not thinking through thoroughly what you need or by buying low quality you’ll also more likely want an upgrade at some point. Consider carefully what you need, and budget to get the long-lasting version that’ll save you money in the long run, while also helping the planet.

Stick to the quantity you need too. “Don’t buy 5 of them because you got a great deal,” Brad adds.

Finding the best performing layer for your needs and keeping it in use for years is much better than a lower performing garment that you don’t end up wearing, especially as it’s not easy for brands to always use sustainable materials for all cycle clothing product types.

Brad explains: “The most difficult segment [for finding environmentally friendly alternatives] is laminates - hardshell and softshell fabrics where multiple layers are laminated together to create a waterproof/breathable shell.

“While more development is ongoing to create more sustainable fabrics in this segment, the core of these technologies rely on membranes that aren’t typically recyclable.

“The nature of the laminate also makes them difficult to break down into component parts for recycling.”

Most of these types of fabrics further rely on DWR treatment to keep their water shedding breathability functioning. Brad notes: “Still today the most durable and effective DWR treatments are PFC-based, while there are several companies developing PFC-free alternatives, they need to be re-treated more frequently.”

Based on this, take particular care and consideration when it comes to buying waterproof layers.

Is the product odour-resistant and requires less washing?

“We’re starting to incorporate a lot of merino wool into our socks and base layers,” notes Darren of MAAP. “Wool is a natural fibre and it has natural properties for heat regulation and so we can minimise applying any chemicals.”

A wool product also has a reduced need for washing, and it’s biodegradable too, both of which help reduces its overall impact.

If you are buying something that has natural odour-resistant qualities, it’s then down to you to make sure you’re not just chucking it in the wash with everything else before giving it a whiff-check. Minimising the number of wash cycles you put on can help reduce your environmental impact.

Can it be repaired?

How long can the product be kept in the “in use” phase?

Rapha, for example, has had its free repairs programme in place since 2004 to return items back to their original condition as best it can.

If you are purchasing a product from a brand abroad it’s worth double checking where the repair scheme is based (if they have one). International repairs can accrue a significant carbon footprint, especially when achieved with air freight which brands opt for in order to return the fixed garment to you asap.

Velocio has partnered with like-minded brands in order to open up regional repair hubs to reduce shipping distances for renewing its garments. In the UK, that’s Apidura, who have also opened up its own Revive store for selling used bikepacking bags to increase the lifespan of its products.

If you have chosen your ideal product from a non-UK based brand, and although they do have a repair centre that you could make use of its only in their home country, remember there’s local (and independent) seamstresses and repair shops in the UK that it’d be environmentally better to turn to, even if you do have to front the cost yourself.

How does the brand deal with reducing waste?

“Our goal is to have no waste,” says Darren of MAAP. “But we do have waste and that’s part of producing products—what we’re trying to do is minimise that wastage.”

Working with mills the brand knows it can get better yield-age from the fabric with is one way and its new OffCuts Program is another.

Using leftovers

“OffCuts is something we will continue with but its done as a way of trying to use the fabrics, and that’s why you’ll see this limited amount of them,” Darren notes.

“In a way this is cool for customers because they’re getting something there might only be 200 of, but it exists because we don’t want to have excess waste.”

> Review: MAAP Evade Pro Base Jersey

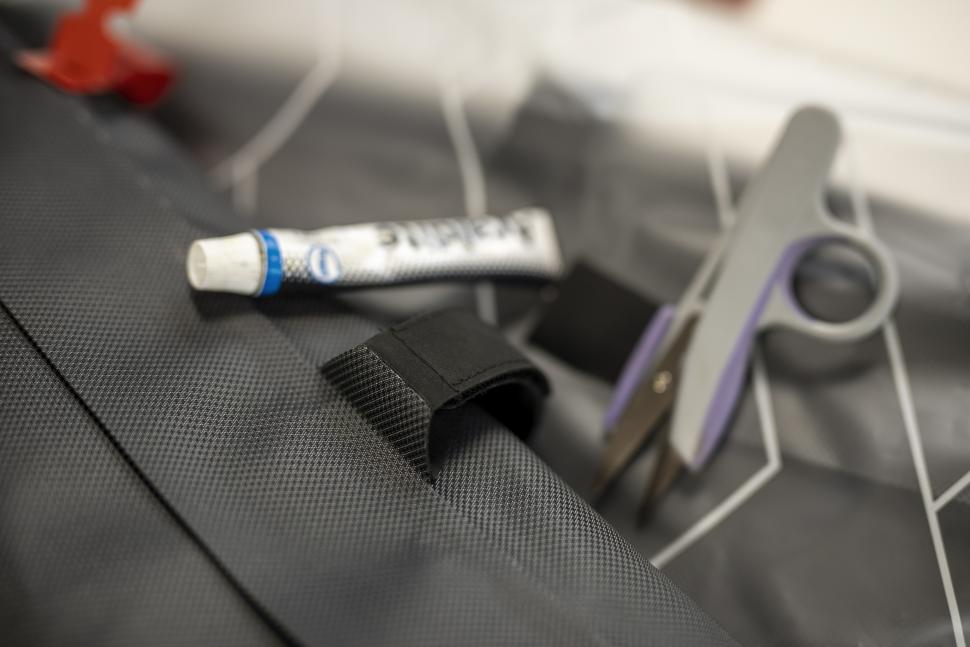

Rapha has its own solution that ties in with its repairs programme. Acknowledging that crashes do happen at any time, Rapha has introduced repair patches for fixing products in its mountain biking range that could get snagged on a branch for example.

Duncan adds: “The repair patches themselves are made from cut outs, leftovers that usually just go to recycling ideally, or landfill at the supplier.

“Instead patches are being cookie cutter style punched-out, adhesive added to the back and then we ship it out with the product so riders can fix it themselves.”

Eco-packaging

What the product turns up in at your door also comes into it. Velocio uses 100% biodegradable packaging and compostable mailers.

“We also use minimal packaging to ensure that whatever is shipped takes up the smallest space possible and can be easily composted at home once the product arrives,” Brad of Velocio adds.

Buying what is needed

Purchasing limited inventory is important too.

“We don’t subscribe to the volume/low cost model. We order conservatively and ensure that every garment we produce is eventually used,” Brad says.

Is it durable?

How many years and months is the product going to be joining you on the road?

“We’re always looking at the quality of our products, looking at the strength of the yarns—because our products are form fitting to the body a lot of our yarns have stretch within them to move with the body,” notes Darren of MAAP.

> Review: MAAP's Women's Evade Pro Base LS Jersey

If you’re buying high quality, in most cases you can expect to be paying a higher price initially, but in the long run with the high quality materials used it’ll likely won’t need replacing any time soon.

Thorough testing by the brand itself is integral to ascertaining quality and the physical durability that comes with it.

Brad explains Velocio’s process: “We start by selecting the highest quality materials, and then we look at lab tests for longevity (abrasion resistance, colorfastness, elasticity, etc) before we even move to prototyping.

“Then we do our own real-world testing to ensure that each fabric and garment can withstand the abuse it’s intended for.

“We continue to test the original product far beyond when it goes into production to follow the lifecycle of each product and ensure that it lasts.”

Design plays a key role in this too. Duncan of Rapha says: “We’ve definitely done some products, when we really tried to push the limits on how light we could make it,” Duncan notes, “but where lightweight-ness starts to butt up against not being durable enough, then we tend to take the decision to choose durability over lightweight-ness.”

> Review: Rapha Men's Commuter Lightweight Jacket

As enticing as a super lightweight weather-resistant layer may sound, also ask yourself if you really need it to be that light. For example, do you ride with a handlebar bag which a slightly heavier and bulkier layer can be stuffed inside?

Chances are a lightweight layer won’t be quite as durable, so consider your use cases and work out if it’s worth risking the shorter life span. Reviews such as ours —with a durability score out of 10 as well as a further explanation detailed in the box below—could help you determine this as well.

Is it going to go out of fashion?

As well as physical durability, there’s also emotional durability. “You can make a product that will last for lifetimes, but the biggest thing that tends to make us want something new is the emotional durability of something,” Duncan of Rapha points out.

“We fall in love with something, we want a bit of a refresh, we want something new to make us feel like we’re making progress.

“That’s okay, but not when it has been engineered to do something like a shorter type of timeframe—that’s called psychological obsolescence.”

“Is the business pulling those psychological levers to pre-emptively shorten the lifespan of their products, just to make you buy more,” Duncan asks, and answers, “to which I say Rapha doesn’t.”

There are portions of products that Rapha does that are seasonal and there are portions that are timeless such as its Classic collection.

> Review: Rapha Classic Jersey II Men's and Women's over here

“That’s not to say that every business needs to have 100% timeless designs everywhere because then everything would look the same, and there wouldn’t be that excitement for that design point of view.

“Products we have that are inspired by history and have a story to them we believe have a greater emotional depth, and that means people are going to want to hold on to them for longer, as opposed to making something that’s purely a trend driven design.”

Before you buy that ‘cool’ stripey jersey, remember that not before long it’ll end up in the back of your drawer along with all your fluro kit from the 2000s.

Can it be recycled or composted after you’ve finished with it?

There’s the end of life phase of the product to think about too.

Rapha is aiming for 50% of its production volume by 2027 to be compostable or recyclable at the end of life. “It’s the longest target in terms of distance away because it’s so hard,” Duncan of Rapha adds.

The natural fibres would go to the compostable route, while all the synthetic fibres go down the recyclable route.

“We already have some products such as the Core Jersey which is 100% polyester and could technically be recycled into polyester to turn back into the Core Jersey—you get a circular flow of materials and we’d like to achieve that at scale.”

Looking to understand this process more? There’s two major forms of recycling, mechanical recycling and chemical recycling, and each have their pros and cons across costs, quality and environmental impact.

“If you buy something that says it’s been recycled, chances are it was once a water bottle that has gone through a machine that shred its up, reheats it and then re-pelletises it,” Duncan explains.

“Mechanical recycling is quite a harsh manual process and because of that you lose certain qualities of the polyester that was there before,” but Duncan admits, “it can be done so well now that we’re not noticing any reduction in performance across any of the materials that we’ve transitioned over.

“That said, if you were to recycle something through chemical recycling which involves dissolving it in a solution, separating it and then re-extracting it, you would have something that quality wise was just as perfect as the first time you did it, which is quite exciting.

“The issue is it can’t be done at scale and it’s incredibly expensive,” Duncan notes.

“But what is exciting about chemical recycling versus mechanical recycling is that with mechanical recycling, you end up recycling a mono-material—it needs to be something that is just one type of fabric.

“Most products that we do, and anyone in the industry does, tend to be a blend of fabrics. Our bib shorts will be something like 60% nylon 40% elastane, which is basically just a recyclers worst nightmare—if we are to recycle that it might be that we have to go through chemical recycling.”

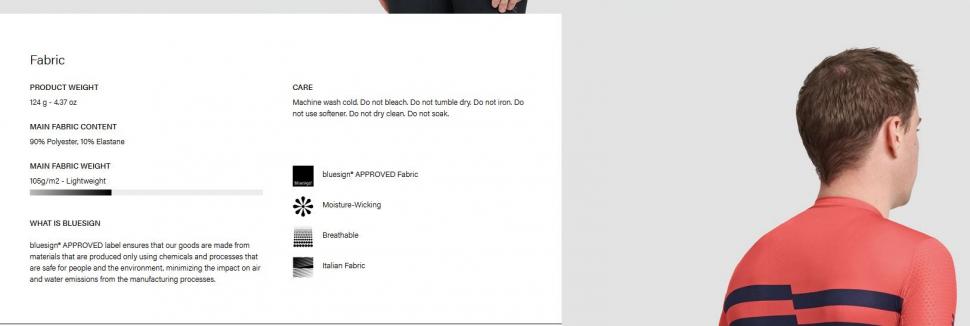

Is it a bluesign or OEKO-TEX approved product?

If you want to be sure that the brand is being honest about its sustainable practices, bluesign acts as an independent verifier and also provides solutions in sustainable processing and manufacturing to industries and brands.

Products can be bluesign approved by fulfilling its criteria which are set to ensure the consistent transparency and traceability of all processing steps down to the raw materials.

It’s an assurance that the companies have “used the best technologies available, used resources responsibly and taken care to minimise the impacts on people and the environment,” says bluesign on its site.

OEKO-TEX is a similar organisation which has its own testing and certification process for consumer safety when buying sustainable.

The ‘Made in Green’ label identifies textiles tested for harmful substances and which have been manufactured under sustainable and socially responsible conditions. You can check the validity of an OEKO-TEX label by entering it into its Label Check over here.

Brands can also become a bluesign partner, in which the independent organisation helps the brand become more sustainable in their supply chain. Darren of MAAP points out, “we are the first cycling company to become a fully functional bluesign partner.

“Using bluesign as a big brother, they guide us and they also have a database of suppliers we can tap into.

“We’re using suppliers that are being governed and signed off by bluesign—it helps us know that a lot of the work of moving towards sustainable processes is already done.

“bluesign will go to that mill, it helps us know the supply chain because you don’t know where those yarns are coming from, how much water was used, when it’s synthetic what chemicals were used—by being a bluesign partner it really helps us govern our supply chain.”

Figuring out what is the most sustainable choice is tricky as it's a complex area, but hopefully the pointers above will help you when you're looking to buy. Just remember the most environmentally sustainable approach is don't buy what you don't need.

To get a better idea of the quality and durability of products, check out our cycle clothing reviews over here.

Anna has been hooked on bikes ever since her youthful beginnings at Hillingdon Cycle Circuit. As an avid road and track racer, she reached the heady heights of a ProCyclingStats profile before leaving for university. Having now completed an MA in Multimedia Journalism, she’s hoping to add some (more successful) results. Although her greatest wish is for the broader acceptance of wearing funky cycling socks over the top of leg warmers.

Latest Comments

- Rendel Harris 2 sec ago

As what you have said is demonstrably untrue, given that the event is organised and has been for the last four years by a professional events...

- chrisonabike 28 min 25 sec ago

Accessibility issue. Of course by necessity / co- evolution the Dutch generally provide a fairly "one size fits standard bikes" parking solution -...

- Kapelmuur 39 min 11 sec ago

Thanks for the heads up. I wore it the first time the temperature fell below 10C, with a merino base layer. A short ride of about 90 minutes, I...

- Steve K 1 hour 43 min ago

I'm there now too, if anyone wants a follow/wants to follow me. @cyclingtheseaso

- Shepton 2 hours 19 min ago

I totally agree. I used to commute through Long Ashton and only started getting agro from motorists when the pavement was made to be a shared path....

- Rendel Harris 2 hours 42 min ago

She was still there in Greenwich when I cycled past her on Wednesday!

- Rendel Harris 2 hours 53 min ago

It's obviously a very personal thing but if I was in the market at your budget I would take a serious look at the Ribble AllRoad SL Pro, currently...

- Hirsute 4 hours 44 min ago

No driver involved https://www.gazette-news.co.uk/news/24728452.car-crash-station-way-colch...

Add new comment

16 comments

Those looking for the most environmentally friendly, sustainable option should note that this article is posted just one day after World Naked Bike Ride day...

Most ot this is not going to help - sustainability happens mainly by systemic choices - regulation, taxation etc. Not consumer "choice" which is a mirage mostly. CO2 etc the average person is in no position to really assess - or verify the myriad of claims. Organic and fair-Labels are a cesspool of corruption too.

The best choice the average person can make is a choice to NOT buy for superficial reasons. Buy what you only NEED.

If you do buy, seek 100% wool, and designed to last, not just be trendy . If it must be synthetic buy something that is well built and designed to last.

But mainly your vote in elections is more relevant if sustainability is the objective.

Spot on - especially the bit in bold

I was a textile chemist in a previous life. Textiles are inherently environmentally expensive. Organic cotton is not necessarily nice, recycling polyester generally produces an inferior fibre.

Even wool requires lots of water to process and the waste scouring liquor is not nice, The world could never produce enough wool to clothe itself.

Dyes are petro-chemical based and their application is water and energy hungry.

Don't consume, but when you do buy something that will last for ever.

The future is.... boring?

I confess I struggle with seeing wool as environmentally friendly. Surely the farming of sheep was historically a reason for de-forestation. Grazing is not good for biodiversity and most rewilding projects, at least in this country, would probably seek to reforest some of this land. However, I am not suggesting I'm an expert and am happy to be educated on the subject.

I am sure that there are already enough plastic bottles on the planet that can be recycled but I appreciate that it's a bit more complicated than that.

I would have also been interested in learning more about the new more sustainable fibres like bamboo and seaweed and whether these are options going forward.

Everything we use is either grown, or dug out of the ground.

Things which are grown are more sustainable, there is not an indefinate supply of things to drag out from under the ground and also those things tend not to be biodegradable.

There may be an issue of scale for animal products such as wool, where there are so many people the space required becomes problematic.

However if the total number of sheep being farmed is not increased due to the use of wool, this argument falls down as these are sheep that already exist for food.

Of course if the entire population went vegetarian there would be a different answer.

Ah yes, I appreciate that I am coming at this from a vegetarian perspective but in this context I think we all know that beef and lamb are, in general, the least sustainable sources of protein and something I think needs to be addressed. I think there was already an article that considered why cycling is less sustainable if we fuel on Burgers so I'm not going to get preachy

I think also it is very difficult for governments to get to grips with current deforestation in Brazil (at least in part for beef production) whilst not considering historic deforestation in New Zealand for example.

You are correct, but absolutely everything comes with an environmental cost.

Nowadays sheep are often grazed on uplands that could not be used for anything else. The downs in southern England have a much valued, biodiverse ecology which has been produced by sheep grazing. As you say the damage has already been done.

Wool is a beautiful fibre that really meets cyclists needs in many ways, but a woollen jersey will never last as long as a polyester one.

PET (polyethylene terephthalate - polyester) bottles can be recycled into fibres for the textile industry. The process involves melting the polymer and then extruding it into fibres. This shortens the length of the polymer chains which produces weaker, hairier fibres. Most recycled polyester is a mixture of recycled and new materials. You cannot recycle indefinitely

Bamboo is chemically similar to cotton. The bamboo is dissolved in nasty chemicals, regenerated as fibres then processed like cotton.

I don't think alginate fibres are produced any longer, but I may be wrong.

Sorry for the lecture.

Still not clear why fossil-fuel based fabrics are better than natural. Seems like you took that at face value, which one of your interviewees suggests not doing, of course.

Raw material for fabrics need to be farmed and things like cotton are incredibly resource hungry - vast amounts of water are diverted away from existing ecosystems in order to irrigate cotton fields adequately and often require chemical encouragement to maximise yield, "natural" doesn't always equal environmentally sound

As a footnote to the Rapha/MAAP advert above, Everything both companies order as far as I am aware is from factories in China... on the other side of the world and then shipped to the UK and Australia using marine diesel, the most polluting fuel or air shipped which is even worse.

Is clothing made locally like from Lusso, who design and manufacture in Manchester not have the least Environmental impact?

Lots of good stuf inthis article. I didn't see mention of what happens to artificial fibres that come out of garments every time they're washed or they abrade. Long term a huge source of microplastics in the seas surely?

Depends where Lusso import their fabrics from, shipping a pallet of material (~10% of which will be waste) is just as resource hungry as a pallet of finished garments

I would love to say yes, but 80% of Lusso's CO2 impact will be in the extraction and production of material, the same as Rapha. Global shipping does of course add to the footprint but not as much as any of us would like to think.

I was watching a program on international shipping a while back, and in cost terms it was cheaper to ship jeans across the world in a container than from the container port to the distrubation centre and to the store. Now of course not all that cost would be in fuel, but those huge container ships are very efficient, even though they are burning filthy fuel.

I may end up looking like a bum, but the most environmentally benificial thing is to wear your clothing until it falls apart, then sew it up or attempt a repair and then wear it some more. My gloves, which often (disapointingly) need sewing when quite new, spend their last few months/years patched with fabric plaster sticky, hobo chic...

"Efficient" = polluting and paying no taxes on a Liberian or Panamanian post box shell company. Tragedy of the commons right there..

I think this illustrates the difficulty for consumers quite neatly. I have no idea which of you is right - long slow ship journey with significant scale or shorter, faster transit by truck. From your posts I know both of you are well informed.

Buy less stuff seems to be the only course of action that is definitely right - and repairability is a big part of that. To be fair to some retailers, they get this: Galibier in addition to those above.

Go shabby chic as it marks you out as a) not a newbie b) not in thrall to fashion c) this fast despite old kit d) only this slow due to old kit.